Of the various characteristics of society normalized by progressivism, one of the least investigated is its propensity for constant dichotomy. The faces of this propensity are multifaceted: anti-smoking propaganda and at the same time pro-cannabis campaigns, anti-sexualization propaganda of women's bodies and at the same time pro-sex-work and pornography campaigns everywhere. Campaigns against the flood of ultra-processed foods and at the same time campaigns for the large-scale adoption of synthetic meat or insect flours (both feeds that require heavy industrial processes). Progressivism consists of an endless series of these doublethoughts, an endless series of gaslighting campaigns having the ultimate goal of a social redefinition in the sense of fluidity. In the list of various dichotomies we can undoubtedly also include that concerning the concept of evaluation and judgment. All progressive rhetoric rails, at least in the first instance, against the practice of judgment, here understood as the faculty of judging something or someone. This is a long-standing struggle: after decades of stoking prejudice, seen as the natural habitat of discrimination and exclusion, the war has been directed toward judgment and evaluation tout court.

From fighting prejudice to fighting judgment

People, in short, not only have (would have) the right not to be pre-judged, but also should not be judged or evaluated in any sphere. Never before has judging been seen as the antechamber of discrimination, when not violence. The phrase “Who am I to judge?” is perhaps the most popular one ever uttered by Pope Francis, not surprisingly the most beloved pontiff among progressives. The fight against judgment, which began on the streets, where it is now considered offensive to smile (let alone laugh) at the most bizarre gender-free gimmicks in the area of clothing and hairstyles, is itself a child of the fight against the concept of limits and boundaries. What does it mean to judge something or someone? It means providing the judging, and thus often the judged, with coordinates.

What does it mean to make a judgment

To provide a judgment, to evaluate something or someone, means to attribute, to what is being judged, coordinates with respect to a goal to be achieved or a table of values; it means, in a nutshell, to understand where that something or someone stands in relation to something or someone else. This is where the radars of progressivism are activated. In the progressive Weltanschauung, there is no worse sin than asking where and when, about anything and about anyone. We are nowhere and the past, as well as the future, has no citizenship, only the eternal present and the eternal here exist; progressivism is a cosmology of the hic et nunc.

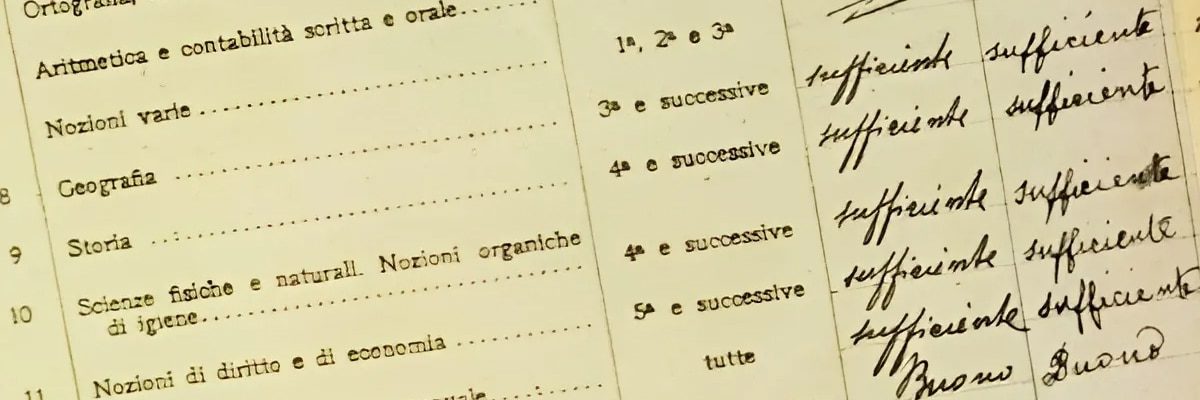

Returning to school ratings

As always, schools prove to be the main focus of this cosmology, and the fight against every judgment, every grade, has always been an important trench for progressive thinking. Once again the problem would be the eminently “discriminatory” value of the grade (or judgment), the meaning of which is openly defined as “punitive.” Leaving aside the fact that adult life is, as it often is already in childhood, full of punishments (whether inflicted by state authorities, family or simple social life matters little), several elements resurface here. On the one hand, all the classical baggage of woke utopianism, on the other hand, the blatant dichotomy that emerges once one leaves behind the doors of the educational institution. The new bill of the Meloni government that brings back, in elementary school, the “summary judgment,” thus retiring the descriptive one, has uncovered this Pandora's box, triggering the indignation of the choribunds of inclusion at all costs and the grade prohibitionists.

The petition

A petition that has collected about eight thousand signatures (few, in a country of sixty million inhabitants), with among them those of illustrious names from so-called civil society, from Moni Ovadia to Father Alex Zanotelli, from Luca Zingaretti to Alessandro Bergonzoni, will soon be forwarded to none other than the Head of State, with the declared aim of scuttling the government measure. The reasons for this uproar have already been examined, but the question that arises is another: how is it possible that the signatories of the petition, alongside numerous teachers, educators and ordinary citizens do not see that, never before have assessments and grades been as ubiquitous as they are today?

Grades everywhere but school

The daily life of any citizen of a country not only Western but, one might venture, modern, is peppered with judgments and grades: suffered and bestowed, consulted or graded. Increasingly, work performance is evaluated according to rigid parameters of productivity and profitability just as our financial reliability is ruthlessly assessed, often in a punitive and exclusionary manner, by banks and lending institutions. The most varied types of smartphone applications are constantly asking us for ratings and judgments: about the last restaurant we ate at, the museum we just visited, the square we walked through an hour earlier, or the courtesy of the delivery man who just delivered a book, a pizza, or a technological device (which we chose from among many after consulting the ratings and reviews of other users).

A school of weakness?

We will be, and already are, evaluated all the time; what is the point, then, of waging war on any evaluation practices within the school? These are not, it should be noted, exaggerations on the part of the writer: the abolition of grades and judgments of any kind is truly the North Star of school progressivism. The “why?” question, in light of a society that is instead fiercely grading and excluding (albeit on different fault lines than those denounced by progressivism), acquires even more significance. What preparation for life can a school that neither grades nor makes judgments provide in a fiercely grading society? The answer seems obvious: none. The individual unprepared for judgment is the only possible product of a school that does not judge. In a society that is increasingly adversarial, to be unprepared for judgment is to be unprepared for conflict, that is, to be weak. What if it is precisely the creation of weak citizens, unfit for conflict, that is the real end of it all?

Research fellow at the Machiavelli Center. A philosophy scholar, he has been working for years on the topic of the revaluation of nihilism and the great German Romantic philosophy.

Scrivi un commento