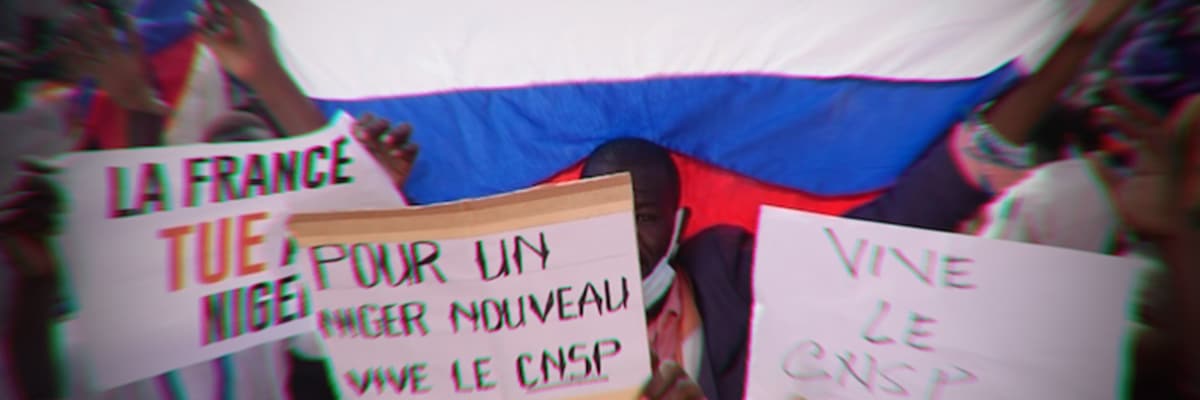

Niger's military forces consummated a coup against President Mohamed Bazoum on July 26. The mastermind of the coup emerged in the following hours, when portraits of Vladimir Putin and Russian tricolors began appearing on Niger streets in the hands of supporters of the new junta.

The Economic Community of West African States, which has a collective military device - the ECOMOG - did not recognize Bazoum's dethronement and sent, in concert with the African Union, an ultimatum to the putsch's perpetrators. But a multinational operation in Niger, whose fledgling government has already received the support of Guinea, Burkina Faso, Mali and the Central African Republic, could pave the way for scenarios of widespread anarchy likely to greatly impact both regional and European security.

The Coup Belt

The coup in Niger is the latest in a series of events that has affected the geostrategic Sahel region and its surroundings over the past three years, giving rise to a "coup belt" that stretches from the Red Sea to the Atlantic Ocean and is considerably affected by Russia's influence. Indeed, most of the overthrows that have taken place since 2020 in this area see the involvement of Moscow assets and/or proxies, such as military personnel linked to Russian Defense, GRU advisers, Wagner Group soldiers, and fighters of North African and Middle Eastern origin.

The episodes-key to the season of instability that has enveloped Sahel and its surroundings are the following: eight coups d'état (Mali 2020, Mali 2021, Guinea 2021, Sudan 2021, Burkina Faso 2022, Guinea Bissau 2022, Burkina Faso 2022, Niger 2023), five coup attempts (Niger 2021, Sudan 2021, Mali 2022, Sao Tome and Principe 2022, Gambia 2022), two near-civilian wars (Central African Republic, Sudan), and the killing of a head of state (Idriss Déby, 2021).

The storm of instability curiously began in 2020, a year after the Kremlin's official return to the Sub-Sahara-emblematized by the launch of the first Russia-Africa summit-and increased in intensity with the war in Ukraine. The relationship between the Sahel and Ukraine is not coincidental: the satellization and/or destabilization of the former is used by Moscow to circumvent the cordon sanitaire created by the West in response to Russian aggression of the latter.

The strategic nature of the Sahel

The Sahel is the most underdeveloped arc of Africa, as well as the most vulnerable to desertification, but it is also a repository of riches, particularly fossil fuels, precious metals, and strategic minerals. Its location, being the link between North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa, makes it a key junction within illegal migration routes. The weakness of the regional states, the most fragile on the entire continent, makes it a blizzard of gray areas where drug traffickers, terrorist organizations and slavers proliferate.

Owning the keys to the Sahel is tantamount to having control of some of the most important routes used by migrant smugglers to facilitate illegal flows to Europe. This is the reason behind the European policy of border externalization, which has historically seen Sahelian states as the first line of defense against illegal immigration and North African states as the second.

The coup belt has undermined the entire European policy of externalizing borders, having destabilized the EU's most extreme external border in whole and created a chain of satellites deployed with Russia. The risk is that Moscow will use the coup belt to militarize migration flows, opening the Sahelian floodgates for the purpose of putting extraordinary pressure on Europe's borders in North Africa in the hope-expectation of gaining concessions from Brussels - a model that may work, as it was already tested by Turkey last decade.

Niger's importance

Niger is one of the pivots of the Sahel, and its strategic importance, iconized by the presence there of significant French military equipment - about 1,500 soldiers - derives from geographic and economic reasons.

This country is indispensable for the containment - or the unleashing - of migratory flows originating in West African coastal states, and its positioning in the international chessboard can support or undermine European efforts in the area of energy security.

The European Union, which is looking to diversify its portfolio of natural gas suppliers, has played a key role in speeding up negotiations between Algeria, Niger and Nigeria for the construction of the so-called Trans-Saharan Gas Pipeline. Infrastructure that, if built, could pump as much as thirty billion cubic meters of gas a year into the Euromarket. Russia's goal is to likely enter the construction of the pipeline, replacing France's Total - which is very active in the region - in order to continue to exert influence, albeit indirectly, in European energy balances.

Niger also owns the world's fourth largest uranium reserves - but surveys suggest that other deposits are waiting to be discovered - and is the main wholesaler for the European Union, which has turned to it to supply a quarter of its needs in recent years.

The uranium issue is particularly acute in France: 15 percent of the uranium used in the fifty-six transalpine nuclear power plants is of Niger origin. Two months before the coup, in May, the Elysée had managed to extend the rights to exploit the Somair mine until 2040. But the new junta tore up the agreement, blocking the export of gold and uranium to France.

With the satellization of Niger, the most important of the Sahelian belt countries, the Kremlin could complete what political scientist Salvatore Santangelo has called the "energy encirclement" of the European Union: Russian gas coming in through the (Mediterranean) window after the (Baltic) door has closed.

The need for a new strategy for Africa

History teaches that coups that do not enjoy popular consent and the support of the apparatuses are not likely to last long. Military regimes in the coup belt are unlikely to create better living conditions for their inhabitants, but for an indefinite period of time they will nonetheless boast a rather large support base: discontent over the pollution of multinational corporations and resentments over yesterday's and today's colonialisms were and are spread like wildfire across Africa.

Emmanuel Macron accused Russia of encouraging the putsch season by means of high-impact cognitive operations that, making use of Russian state media, local media, influencers and social media, would exacerbate past tensions and spread Francophobia in and around the Sahel. The Elysée accusations rest on a kernel of truth, but they ignore the fact that the Kremlin fueled, not created-the difference is substantial-a grudge that had been brewing for a long time and was waiting to be exploited.

It is no coincidence that Russia's subversive operations show higher success rates in the countries that make up the French sphere of influence in Africa, popularly known as Françafrique. Indeed, these are the countries where postcolonial resentment is more present, genuine and entrenched than elsewhere, and this greatly facilitates both the conduct of regime change and the growth of anti-Western political forces.

The European Union is trapped in the cage of economism: there is a widespread belief that import-export is synonymous for influence. Africa shows that international politics does not always respond to the laws of economics, because if it did, the European Union would be able to exert a greater impact on continental dynamics than the United States, China and Russia.

Western decision makers tend to underestimate Russia's capacity to influence, in Africa as in the rest of the world, because of the application of economistic criteria to their reasoning, which results in the production of reductive, simplistic and, often, erroneous analyses of reality.

Russia has never been a trading power, and the means it employs in Africa to expand its influence are primarily intangible in nature: culture, information, history, universities. Russia invests in brains to get to resources: it trains influencers, trains journalists, and trains future leaders-African students in Russian universities increased fivefold between 2010 and 2021, from six thousand to thirty thousand. Russia invests in perpetuating the memory of the Soviet contribution to the independence of African countries, which is fuel for the capillarization of an "intergenerational anti-Westernism."

Encouraging ECOMOG to intervene militarily in Niger to restore the status quo ante could be successful, leading to the downfall of the junta, as it could trigger a regional crisis involving ECOMOG members and coup belt components.

Best-case scenarios contemplate a return of the previous manu militari executive or a decision by the junta to call new elections in the near future. Worst-case scenarios involve a civil war, a moderate regional crisis, or a major Central African war.

It is time for Italy to learn from French mistakes and keep in mind that the tribalization of North Central Africa is the latest perverse consequence of the decision to support regime change in Libya in 2011 - original sin that uncovered the African Pandora's box. In and around the Sahel, Europe's physical and energy security are at stake; further mistakes cannot be made.

Geopolitical analyst, foreign policy consultant and author. Graduate in Area and global studies for international cooperation (University of Turin), educated between Italy, Poland, Portugal and Russia. Specialized in hybrid warfare, Latin American issues and post-Soviet space.

Scrivi un commento