by

To judge the value - positive or negative - of immigration for Italy, three aspects must be evaluated primarily: demography, culture and economy. For the sake of brevity, we have decided not to deal with the issue of ethnocultural incompatibility between profoundly different peoples; we limit ourselves - trivially - to point out how it is easier for Italy to assimilate Romanians and Ukrainians than non-European immigrants from Islamic, animist and tribal cultures who have no intention of amalgamating with the natives: they emigrate to Europe because they are attracted by work and subsidies.

The economic issue is - almost always - the main justification for opening the borders to immigrants: they do the jobs that natives no longer want to do, they pay us pensions, etc. To the economic justification, several objections must be made.

1 - “We need people to pick tomatoes at €2 per hour”

From a strictly moral standpoint, the economicist approach is inherently racist: the immigrant is seen as a useful tool to replace natives in the most strenuous jobs, (perhaps) paying them less. Of course, this approach is natural: immigrants have been exploited for the same reasons since Roman times. However, admitting this, immigration advocates should not cloak themselves in moral superiority since the economic justification is de facto an implicit acceptance of slavery. The immigrant who works to pay the pensions of the natives is serving the natives. There is more. If the children of immigrants were to integrate, no longer doing the “menial jobs” of their parents, but - labor-wise - reaching the same level as natives, this would cause a new demand for immigrants (willing to do the work that both natives and second-generation integrated immigrants no longer want to do), making the country dependent on immigration.

2 - No, immigrants will not pay our retirements

In the economic balance of immigration, not only the income (the contributions paid by immigrants) should be considered, but also the expenditure (the costs of immigration: reception, assistance, justice, remittances, etc.). The Leone Moressa Foundation publishes an annual report on the economic impact of immigration. The latest one, published in October 2023, based on data from the Ministry of Economy and Finance, estimates that the net contribution of immigrants was 1.8 billion. Well below the figures bandied about by the press and left-wing politicians, who tend to look predominantly at incoming items and much less at outgoing ones.

“The trend we have observed in our reports is that the economic balance of immigration is generally always positive”, we read in the report. “The reason is mainly the fact that the foreign population in Italy is generally young and of working age, and therefore has little influence on the two main items of public spending, namely health care and pensions”. It is pointed out how wrong it is to say that “immigrants pay our retirement pensions”; in truth, “Foreign nationals living in Italy certainly contribute to support our social security system, but in an all in all marginal percentage compared to total pension spending”. We add that the report does not contemplate the contribution of irregular immigration, “At the same time, however, irregular immigrants benefit in marginal terms from the services guaranteed by the state and therefore are not considered in our report”.

Immigrants and denatality: a temporary, double-edged solution

Immigrants and denatality: a temporary, double-edged solution Gian Carlo Blangiardo, a demography professor at the University of Milan and president of ISTAT (2019-2023), downplayed “a certain commonplace according to which it is only thanks to immigrants - as young people and workers - that it will be possible to stem the phenomenon of growing demographic aging and solve the problem of pensions and the imbalances that are looming on the health spending front. But again, it is good to bring the claim back within its proper boundaries. In fact, if there is no doubt that strong contingents of young people arrive, as they have arrived in recent years, which tend to slow down - though not stop - the growth of the ratio of the number of retirees to the working population, it is also true that in the near future these same young people will be old; and then in addition to the aging produced by those born in Italy-think of the million children of the baby boom of the 1960s who around 2030 will become over 65-we will have hundreds of thousands of people (it is estimated there will be about 200. 000 new cases annually starting in 2030) who without having been born in our country will age here: they will be the “added elderly” in a country of elderly people. The real contribution of today's (still) young immigration is thus-unless we assume gradually increasing but essentially unmanageable inflows-only to give us a little extra time to try to fine-tune the necessary adjustments in the welfare system.

In this sense, even the much-emphasized net immigration surplus - as the difference between payments (of taxes and contributions) and collections (for benefits and welfare spending) - may provide some relief to the public accounts today in cash terms, but it does not amount to a surplus balance with respect to the accrual principle. Social security payments, which today seem to far exceed the corresponding spending, represent only a loan; they are a cash advance of which immigrants will legitimately demand repayment, in the form of benefits and pension checks, as early as over the next 2-3 decades". In short, those who argue that “immigrants pay us retirement pensions” need to be reminded that foreigners also age and consequently will - rightly - demand a retirement.

“Despite only making up 8.5 percent of the population...”

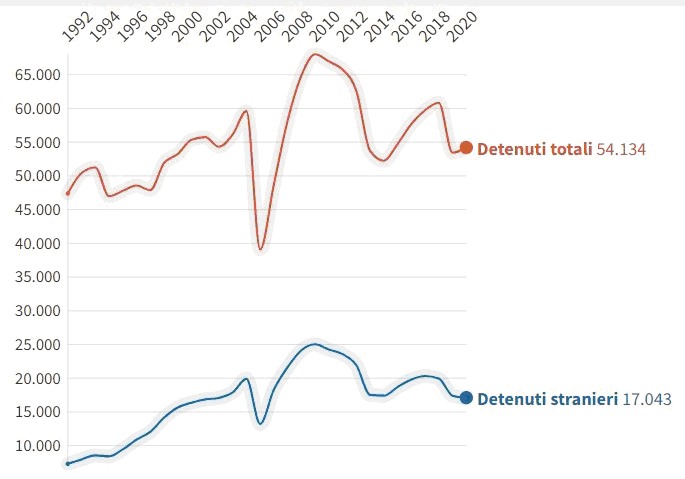

Tying the economic issue to security, we note -on 2021 data - that out of 54,134 inmates, 17,043 were foreigners, 31 percent. Since foreigners accounted for 8.5 percent of the population, it follows that foreigners are 5 times more likely to be jailed than Italians. To these must be added 900 inmates who were born abroad but were granted Italian citizenship.

Breaking down the inmates by nationality shows that:

| Inmates' nationality | Probability of detention compared to Italians |

| -Europe | 3 times higher |

| Albania | 6 times higher |

| Romania | 3 times higher |

| -Africa | 12 times higher |

| Algeria | 34 times higher |

| Morocco | 12 times higher |

| Nigeria | 16 times higher |

| Tunisia | 26 times higher |

One inmate costs the Italian state €137 per day, which means that the 17,043 foreign inmates in 2021 cost us nearly €853 million. With some fluctuation on the percentage, in 2010 foreign prisoners made up almost 37 percent of the total, foreign prisoners increased from 7,237 in 1992 to 17,043 in 2021.

Graph prepared by Italy in Data, Italy's prisons, italiaindati.com.

Conclusions

Can a temporary economic benefit outweigh the demographic and cultural subjugation of natives? This is the fundamental question. It is not necessary to cite the endless crime cases involving non-European immigrants. Stopping at the economic balance sheet is a superficial approach that condemns Italy - and Europe - to decline. Everything is aggravated when, under the guise of pensions and good feelings, a real immigration business is set up, which, relying on a paramilitary system, enriches - on the skin of migrants and Italian taxpayers - only private individuals.

Sources:

Fondazione Leone Moressa, Rapporto annuale sull’economia dell’immigrazione. Edizione 2023. Talenti e competenze dell’Europa del futuro, il Mulino, Bologna, 2023.

Blangiardo, Gaiani, Valditatra, Immigrazione. Tutto quello che devi sapere, Aracne editrice, Canterano, 2016, pp. 26-27.

Francesca Totolo ha elaborato i dati dell’ISTAT nell’articolo “Allarme criminalità straniera, gli immigrati rappresentano il 31% della popolazione carceraria in Italia: vi mostriamo tutti i dati”, Il Primato Nazionale, 27.01.2023.

Quanto costa un detenuto allo Stato italiano?, poliziapenitenziaria.it, 08.10.2022.

Foto: CC 2.0 Stefano Corso

A maverick of nonconformist thought, he writes for several newspapers and blogs. He is interested in demographic dynamics, history, geopolitics and "fashionable ideologies."

Scrivi un commento